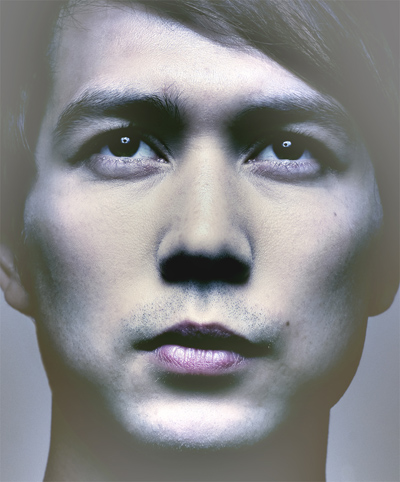

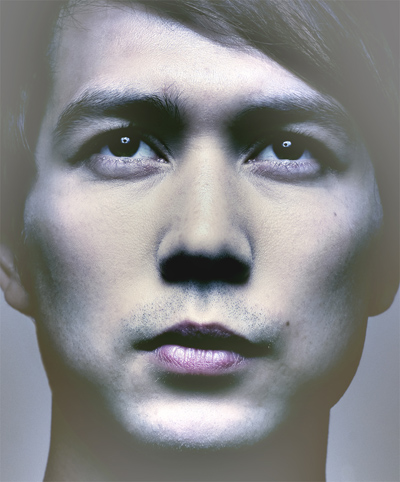

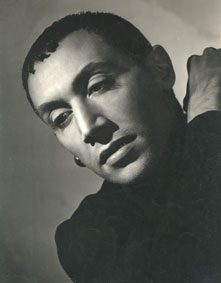

Tommy Franzen needs no introduction. Beginning his dance training in Sweden, he was only ever interested in street dance classes. Tommy then began working professionally at the young age of 14 in the musical Joseph, hopping from musical to musical before embarking on a 3-year performing arts diploma course at the Urdang Academy in London, for which he received a scholarship.

Tommy Franzen needs no introduction. Beginning his dance training in Sweden, he was only ever interested in street dance classes. Tommy then began working professionally at the young age of 14 in the musical Joseph, hopping from musical to musical before embarking on a 3-year performing arts diploma course at the Urdang Academy in London, for which he received a scholarship.

He is probably mostly recognised as the runner-up of BBC 1’s So You Think You Can Dance 2010, but other dance fans may have spotted him in Mamma Mia – The Movie, The Pepsi Max Advert Can Fu and the Handover Ceremonies at Bejing Olympics 2008.

Having worked professionally as a performing artist for 16 years, Tommy has recently delved into choreography, for example working on ZooNation’s Some Like It Hip Hop, performing in the show as Simeon Sun. Currently Tommy is working with the Russell Maliphant Company and is touring internationally with the show The Rodin Project.

This year Tommy was nominated for an award at the National Dance Awards in the “Best Male Performance (Modern)” category for his efforts in Goldberg at The Royal Opera House and Blaze at Sadler’s Wells Peacock Theatre. Tommy has also been nominated for an Olivier Award (2012) for Outstanding Achievement in Dance.

Here Tommy talks about his dance career to date, the joy of rehearsals, and his biggest inspiration, Bruce Lee.

When did you begin dancing and why?

I started dancing at age of 11 back in 1992. My sister, Elena, was taking classes and performing for a man called David Johnson who came from California to Sweden to open up a dance school. That’s the first time I had seen anyone dance hip hop dance styles and it grabbed me straight away. They caught me sometimes doing the Robot, basically imitating them so Elena thought that maybe I should try and go to a class. I did, and after the first class I never wanted to go back again as I thought I was the worst one in there. My dad and Elena were surprised and luckily convinced me that I was actually the best of the lot! So I changed my mind in a second, went to the next class and have never looked back since.

What were your early years of dancing and training like?

I started with classes that incorporated locking, popping, general hip hop and some tricks. That was at David’s dance school ‘Crazy Feet’ in Lund, Sweden.

How does that compare to now?

Through the years I’ve danced many styles but nowadays when I go to class it’s either hip hop, contemporary or ballet.

Have you always been interested in choreography?

No, I haven’t always been interested in choreography. I hadn’t thought of doing it really when my first opportunity came along and I choreographed for a show called Blaze, which we played at the Peacock Theatre in London and is now touring the world. Since then I’ve choreographed for Some Like It Hip Hop and Cher Lloyd. It’s not my main focus but I do really enjoy it.

What would you say was your choreographic triumph?

Definitely Some Like It Hip Hop. Saying that, I think Blaze put me on the map but I did a lot more for SLIHH and I’m more proud of my efforts in that show. We’ve been nominated for the choreography several times so we must’ve done something right!! The other choreographers are Kate Prince and Carrie-Anne Ingrouille with additional choreography by Duwane Taylor and Ryan Chappell.

How long have you been performing and choreographing?

I’ve been performing for 21 years and choreographing for 3 years.

What is your favourite role you have danced and favourite choreographer you have danced for, and why?

I must say my character Simeon Sun in Some Like It Hip Hop has been a right ball to play: so much fun. Lots of acting and very challenging dance wise. I’ve only got myself to blame for that! I would probably say that there are three favourite choreographers I’ve worked with. Kim Brandstrup, Russell Maliphant and Kate Prince, who are all very different and very good in their own field of work.

What do you like most about rehearsals?

The best thing about rehearsals is the creation period. You are being creative and you train hard. Then we you start performing then things are pretty much set in stone but you get the pleasure of sharing with an audience. I love the feeling of dancing in front of an audience.

What is the best part about dance?

It’s so much fun!!

Who would you most like to work with, dead or alive?

Bruce Lee without doubt, he’s always been my biggest inspiration.

What’s next for you?

There are a few projects coming up but I can’t disclose anything yet. I will be working with Boy Blue Entertainment on their new show at The Barbican in October. I also spend a lot of time building two businesses at the moment. As dancers we don’t have a pension for when we retire at a relatively young age so I think it’s important to secure your financial future by other means during your dance career.

The prestigious Royal Ballet School announced the appointment of Christopher Powney as their Artistic Director Designate last month, who is due to step into the role in April 2014. The current Artistic Director, Gailene Stock, is sadly unwell, and will retire from her post on 31 August 2014. As a result, the summer term of 2014 will see Powney taking over the running of the School after a transitional period. Jay Jolley will continue in the role of Acting Director and will lead the School’s artistic programmes into the 2013/14 academic year.

The prestigious Royal Ballet School announced the appointment of Christopher Powney as their Artistic Director Designate last month, who is due to step into the role in April 2014. The current Artistic Director, Gailene Stock, is sadly unwell, and will retire from her post on 31 August 2014. As a result, the summer term of 2014 will see Powney taking over the running of the School after a transitional period. Jay Jolley will continue in the role of Acting Director and will lead the School’s artistic programmes into the 2013/14 academic year.

The theatre is a world of mystique, intrigue and illusion, serving to delight and entertain its audience with spectacle, no matter how otherworldly. This tradition of theatre is still upheld in many venues and arts spaces across the country and even across the world, but equally much of the previous spectacle has developed to accommodate the twenty first century. Productions have alternative intents, aiming to shock and provoke audiences rather than provide a successful model of theatre which has been proven to work.

The theatre is a world of mystique, intrigue and illusion, serving to delight and entertain its audience with spectacle, no matter how otherworldly. This tradition of theatre is still upheld in many venues and arts spaces across the country and even across the world, but equally much of the previous spectacle has developed to accommodate the twenty first century. Productions have alternative intents, aiming to shock and provoke audiences rather than provide a successful model of theatre which has been proven to work. Carlos Acosta’s return to the London Coliseum in August is highly anticipated, particularly as the casting and classical repertory has recently been announced, forming Acosta’s Classical Selection. Running from July 30 to August 4, the run is full of huge ballet stars and iconic works.

Carlos Acosta’s return to the London Coliseum in August is highly anticipated, particularly as the casting and classical repertory has recently been announced, forming Acosta’s Classical Selection. Running from July 30 to August 4, the run is full of huge ballet stars and iconic works. As a choreographic work which does not end in death for the main protagonists, Coppélia is a light-hearted comedic ballet, with a narrative which delights audience with its humour, magic and a happy ending.

As a choreographic work which does not end in death for the main protagonists, Coppélia is a light-hearted comedic ballet, with a narrative which delights audience with its humour, magic and a happy ending.

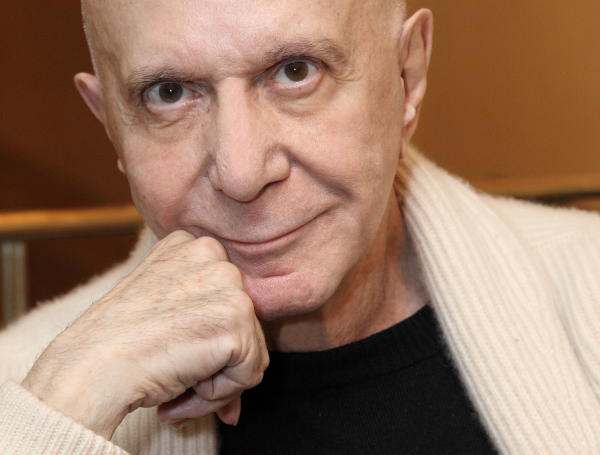

Roland Petit, a choreographer in post-WWII ballet, was responsible for defining a new French chic and erotic frankness in dance, creating many roles for his wife, Zizi Jeanmaire. With July 2013 the second anniversary of his death, there has recently been a Moscow Stanislavsky production of Petit’s Coppélia, receiving mixed reviews.

Roland Petit, a choreographer in post-WWII ballet, was responsible for defining a new French chic and erotic frankness in dance, creating many roles for his wife, Zizi Jeanmaire. With July 2013 the second anniversary of his death, there has recently been a Moscow Stanislavsky production of Petit’s Coppélia, receiving mixed reviews. Whether you are a dancer, actor or performance artist, you will be well aware of the phrase ‘backstage ritual’.

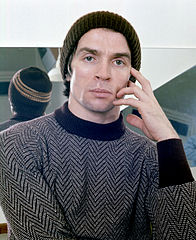

Whether you are a dancer, actor or performance artist, you will be well aware of the phrase ‘backstage ritual’. Following performances of three young Russian men – Ivan Vasiliev, Sergei Polunin and Vadim Muntagirov – there has been some speculation from dance critics as to whether any of these men may become the next Rudolf Nureyev, one of the greatest male ballet dancers of the twentieth century and an extremely charismatic performer.

Following performances of three young Russian men – Ivan Vasiliev, Sergei Polunin and Vadim Muntagirov – there has been some speculation from dance critics as to whether any of these men may become the next Rudolf Nureyev, one of the greatest male ballet dancers of the twentieth century and an extremely charismatic performer. Tommy Franzen needs no introduction. Beginning his dance training in Sweden, he was only ever interested in street dance classes. Tommy then began working professionally at the young age of 14 in the musical Joseph, hopping from musical to musical before embarking on a 3-year performing arts diploma course at the Urdang Academy in London, for which he received a scholarship.

Tommy Franzen needs no introduction. Beginning his dance training in Sweden, he was only ever interested in street dance classes. Tommy then began working professionally at the young age of 14 in the musical Joseph, hopping from musical to musical before embarking on a 3-year performing arts diploma course at the Urdang Academy in London, for which he received a scholarship. Jack Cole, one of the greatest yet least known jazz choreographers is thought of by some as the father of theatrical jazz dance, responsible for the jazz we know today. He was the influencer behind huge choreographic names such as Bob Fosse, with his work reaching the likes of modern dance greats Alvin Ailey and Jerome Robbins. Cole worked to create the style of jazz that is still widely received today, on Broadway, in Hollywood movie musicals and in music videos.

Jack Cole, one of the greatest yet least known jazz choreographers is thought of by some as the father of theatrical jazz dance, responsible for the jazz we know today. He was the influencer behind huge choreographic names such as Bob Fosse, with his work reaching the likes of modern dance greats Alvin Ailey and Jerome Robbins. Cole worked to create the style of jazz that is still widely received today, on Broadway, in Hollywood movie musicals and in music videos.