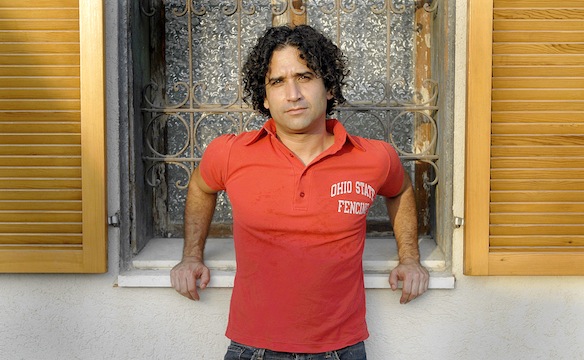

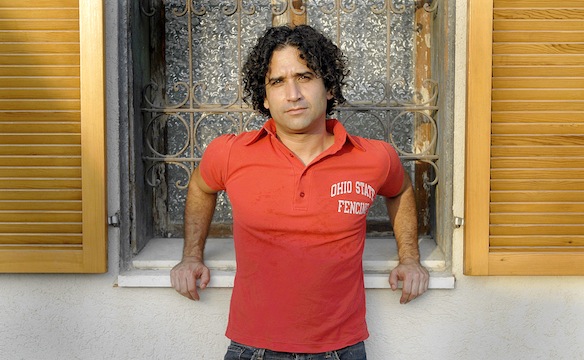

Barak Marshall is a choreographer incredibly sure of his message. From studying at Harvard, to his first choreographed work, to his upcoming commission for Rambert dance company, Barak has an innate sense of communication, both through dance and in conversation. Self-taught, Barak is a choreographic phenomenon, fuelled by humans and the expanse of description in dance.

Barak Marshall is a choreographer incredibly sure of his message. From studying at Harvard, to his first choreographed work, to his upcoming commission for Rambert dance company, Barak has an innate sense of communication, both through dance and in conversation. Self-taught, Barak is a choreographic phenomenon, fuelled by humans and the expanse of description in dance.

When did you begin dancing and why?

Umbilical whiplash!

My mother, Margalit Oved, is a very famous choreographer and a dancer. She was born in the British Protectorate of Aden and after immigrating to Israel she became the prima ballerina of the Inbal Dance Theatre where she danced for 15 years touring the world including performances at Drury Lane and on Broadway. In 1964 she met my father in Los Angeles while filming a movie there. They married and she moved to LA where she taught dance at UCLA and founded her own very successful dance company.

I spent my childhood touring the US with her dance company on a broken down red school bus with 10 hippie dancers and a lot of homemade cheese. In the summers we would return to Israel where my mother would perform guest roles with Inbal. My sister and I slept more on studio and theatre floors than in our own beds. When my mother was not performing my parents went to every dance, theatre and music performance they could.

So, dance was the last thing that I wanted to do. I went to college and in 1993 I graduated from Harvard where I studied Social Theory and Philosophy and planned on going back to law school.

But, in 1994, my mother was appointed Artistic Director of Inbal and my father asked me to help her settle in. Shortly after we arrived, my Aunt Leah – who was a second mother to me – unexpectedly died. I was overwhelmed with grief and every day after sitting Shiva with my family (the Jewish tradition of observing seven days of mourning) I would return to the studio and lock the door. I was afraid that my memories of my aunt would fade so I tried to consciously remember every detail I could so that I would never forget her: her stories, words of wisdom, the way she laughed, cried, cursed, cleaned the floor, cooked, blessed me and sang.

I didn’t know this at the time but one of my mother’s dancers was secretly watching me from a balcony above the studio. At the end of Shiva, she surprised me in the studio and said that she wanted to show me some movement. She showed it me, I told her that it was beautiful and she said, “This is your movement. You should build a piece in memory of your aunt.” So I created and danced in my first work, Aunt Leah, which was a ritual remembrance of her life, her wisdom and her kindness filled with Adenite blessings, sayings, gestures and music.

That’s how I began to dance.

What were your early years of dancing and training like? What was a typical day like?

To this day I still have never taken a dance class. Because I first started in dance as a choreographer I focused on developing my own movement language. I follow a few rules: I create all of the movement on my own body, I try to create more movement than I actually need for the work, I try never to repeat myself and not to allow other choreographers’ movement sneak in.

How long have you been choreographing? Did you start young?

I created my first work in 1995 when I was 27. After running my own company for four years, Ohad Naharin appointed me house choreographer for the Batsheva Dance Company. However, in 2000 I severely broke my leg. The injury was so bad that I couldn’t walk without pain for 2 years. I had to stop dancing completely and moved back home to Los Angeles to recuperate. I thought I would never go back to dance but in 2008, the Suzanne Dellal Centre in Tel Aviv invited me back to Israel and commissioned me to create Monger, my first work in eight years. And I have continued to choreograph since then.

What is a typical day like now?

Even when I do not have a commission to work on I try to spend at least 2-3 hours every day researching ideas and images for future works. I read as much fiction and plays as possible. I struggle through books on theatrical theory and practice, and I scour the internet for plays and dance performances. Of course, I try and drag myself into the studio every day to dance. I’m not always successful.

Do you still take classes? How do you keep on top of your technique?

I think that at this point dance class might get in the way. I create dance theatre – not dance. I am not as interested in the aesthetics of movement. I am interested in the content of movement – not it’s form. Most techniques emphasise form so when I am in the studio I focus on developing and expanding my movement vocabulary. I guess the best way to describe it is trying to create a sign language for the whole body.

How do you begin your choreographic processes?

Before I was a dancer I was a singer and a musician. I’ve studied and performed music all of my life. I think that is the reason that I cannot see a work before I hear it. I really believe the dance begins with music.

So while I do begin a work with a vague idea or fragment of a story that I want to tell, I can only move forward when I hear it. My first task is to find the music that inspires the dance that tells the story. In creating the soundtrack of each piece I usually listen to around 10,000 tracks of music to find the 15-20 pieces of music that eventually make up the final score. That’s not as crazy as it sounds – most of the time I only listen to the first few seconds of a song. If it resonates physically, evokes an emotion or image or relates to a scene or idea that I want to investigate, I will save it to listen to at a later time.

My process involves collecting as many images, stories, ideas, songs, gestures and movements and little by little an image might resonate with a story, piece of music or a movement and create the beginning of a section. Slowly a storyboard emerges and I play with the various parts until a narrative arc emerges.

What inspires you?

People and their struggles inspire me. I’m an optimistic cynic and I see life as a constant struggle against forces – both external and internal – that seek to deprive you of your own free will and strength. All of my works deal with that. Aunt Leah was a piece about an overly kind woman who gave so much to others that she had nothing left for herself. The Land of Sad Oranges was about the danger of sanctifying a land or anything as holy. Emma Goldman’s Wedding dealt with a visionary woman’s fight against a stratified and misogynistic society. Monger is an upstairs/downstairs story about 10 servants controlled by a cruel mistress. Rooster is about a man so afraid of life that he can only realize his dreams by falling asleep. Harry deals with a man who defies the gods, Wonderland is a story about the dead. The work that I have created for Rambert, The Castaways, is a story of 12 deeply flawed individuals manipulated by an unseen master puppeteer.

In reading back over this list I realize that it all sounds quite dark. But I don’t believe in darkness. I believe my works are hopeful and humorous which I believe are the antidote to these forces.

What’s the best part of choreographing?

I love dance theatre because it tells a story, just like a play, film or novel does. I try to tell simple stories, not literal ones, and I am always conscious of it. I am quite jealous of theatre directors because they begin with a text that they can abstract upon.

I try and create the entire text or movement of the work before I get into the studio with the dancers. For me each movement is a word and these form a sentence or text that the dancer is speaking.

This is what I love most about choreographing: searching for the gesture or phrase that expresses the emotion, word or subtext that I want the dancer to speak physically.

What advice would you give to someone aspiring to a career in contemporary dance or choreography?

Be sober.

With rare exceptions I don’t believe that there is such a thing as a career in dance or choreography. Dancers’ careers are extremely short – most spend more of their lives training than they do dancing. Most choreographers are constantly battling to get enough jobs to survive. I know that I am doing better than most choreographers but there isn’t day that goes by when I am worried about paying the bills and consider changing careers.

Don’t get me wrong – I love dance and I love what I do. However, I believe that the dance world suffers from a collective self-delusion. Much of our system of dance education perpetuates a myth: that there is a huge career awaiting you. I have taught dancers throughout the world and time and time again I see a criminal failure to prepare dancers for the harsh economic reality that awaits them, and that’s if they are lucky enough to find a job. And I have seen too many wonderful dancers fall off the deep end when their careers come to an end.

Dancers and choreographers are also complicit in this—we cannot allow our love of dance to blind us to reality.

Again, I love dance, but I think it is time we started to have a serious discussion.

For dancers, my best advice is to understand that unfortunately much of the system and culture of dance focuses on telling you what you are doing wrong. Don’t buy this. You are humans not robots and that humanity is what can make dance so beautiful. And don’t ever allow a choreographer to force you to work through pain.

For choreographers my advice is not to get caught up in the drama (this isn’t easy because the dance world seems to be the last place of work where acting out is still seen as acceptable). We’re creating dance – not finding a cure for cancer – and the worst thing for a creative process is an environment where you cannot play, make mistakes or be vulnerable. You also should work harder than you think possible, create as much as possible and don’t over-idolise your idols. We all have choreographers whom we consider genius, are amazed by their creativity and aspire to be like them. But Emerson said it best: “Imitation is suicide.”

When I first started out my mother gave me some great advice. She said:

- Don’t care what other’s think—this kills creativity.

- Silence the critics inside your head.

- If you work, you will find, if you don’t work, you won’t find.

- Great artists don’t measure themselves by others, they are inspired by them.

- Fail.

For me growing as choreographer is all about trial and error, and more error.

Overall, what is the best part about dance for you?

I cannot think of an art form that more perfectly reflects the beauty and pain of the human condition.

What are you most looking forward to in choreographing for Rambert?

The dancers. They have a level of intelligence, talent and hunger that is rare. Beyond that I have not seen a company that is as ethnically diverse. They bring humanity to the stage and make my work better than it is.

Peggy Lyman Hayes danced with the Martha Graham Dance Company from 1973 to 1988, featuring in works including Lamentation, Frontier and Acts of Light. She is one of the master instructors at the Martha Graham School of Contemporary Dance in New York and is currently responsible for restaging Graham’s works for the Martha Graham Trust.

Peggy Lyman Hayes danced with the Martha Graham Dance Company from 1973 to 1988, featuring in works including Lamentation, Frontier and Acts of Light. She is one of the master instructors at the Martha Graham School of Contemporary Dance in New York and is currently responsible for restaging Graham’s works for the Martha Graham Trust.

Iconic choreographer Hofesh Shechter has been named as the individual to guest direct Brighton Festival 2014. Running from 3 May to 25 May, the Brighton Festival is an annual mixed arts event that takes place across the city. Whilst full programme details will be announced on 25 February 2014, it is already knowledge that the festival will open with Shechter’s contemporary dance company’s new production, Sun.

Iconic choreographer Hofesh Shechter has been named as the individual to guest direct Brighton Festival 2014. Running from 3 May to 25 May, the Brighton Festival is an annual mixed arts event that takes place across the city. Whilst full programme details will be announced on 25 February 2014, it is already knowledge that the festival will open with Shechter’s contemporary dance company’s new production, Sun. Barak Marshall is a choreographer incredibly sure of his message. From studying at Harvard, to his first choreographed work, to his upcoming commission for Rambert dance company, Barak has an innate sense of communication, both through dance and in conversation. Self-taught, Barak is a choreographic phenomenon, fuelled by humans and the expanse of description in dance.

Barak Marshall is a choreographer incredibly sure of his message. From studying at Harvard, to his first choreographed work, to his upcoming commission for Rambert dance company, Barak has an innate sense of communication, both through dance and in conversation. Self-taught, Barak is a choreographic phenomenon, fuelled by humans and the expanse of description in dance. The Chelmsford Ballet Company, an amateur company with professional standards, is holding its annual Let’s Make a Ballet at The Sandon School in Essex on Sunday 20 October 2013. Let’s Make a Ballet is a choreographic workshop resulting in a short ballet production for young dancers wishing to get a taste of what it is like to be choreographed into a ballet production.

The Chelmsford Ballet Company, an amateur company with professional standards, is holding its annual Let’s Make a Ballet at The Sandon School in Essex on Sunday 20 October 2013. Let’s Make a Ballet is a choreographic workshop resulting in a short ballet production for young dancers wishing to get a taste of what it is like to be choreographed into a ballet production. American Ballet Theater has announced a diversity programme in beginning a partnership with the Boys and Girls Clubs of America and regional ballet companies across the country in order to increase the number of minority dancers. Project Plié will offer scholarships to talented young dancers and train dance teachers who work in underrepresented groups and communities, boosting diversity within ballet to reflect the US population.

American Ballet Theater has announced a diversity programme in beginning a partnership with the Boys and Girls Clubs of America and regional ballet companies across the country in order to increase the number of minority dancers. Project Plié will offer scholarships to talented young dancers and train dance teachers who work in underrepresented groups and communities, boosting diversity within ballet to reflect the US population. Matthew Golding, Principal dancer with Dutch National Ballet, is set to join The Royal Ballet as a Principal in February 2014. The Canadian dancer has recently appeared on London soil during English National Ballet’s run of Swan Lake earlier this year in which Golding’s ‘dance’ acting, or lack of, was scrutinised by critics. An expansive dancer with exceedingly long legs, Golding is seemingly the mute prince, unable to express himself through the choreography.

Matthew Golding, Principal dancer with Dutch National Ballet, is set to join The Royal Ballet as a Principal in February 2014. The Canadian dancer has recently appeared on London soil during English National Ballet’s run of Swan Lake earlier this year in which Golding’s ‘dance’ acting, or lack of, was scrutinised by critics. An expansive dancer with exceedingly long legs, Golding is seemingly the mute prince, unable to express himself through the choreography.