The dance discipline of tap has been around since the late nineteenth century, acting as the dance of jazz music. While most of the commercial dance seen in the media is mostly competitive, modern or balletic, tap still holds a firm place in the interests of dancers, and cannot fail to be impressive.

The dance discipline of tap has been around since the late nineteenth century, acting as the dance of jazz music. While most of the commercial dance seen in the media is mostly competitive, modern or balletic, tap still holds a firm place in the interests of dancers, and cannot fail to be impressive.

Tap can be described as both movement and music, as while it is usually performed to music, it also makes its own music, as does other foot-stamping dance forms such as flamenco, Irish dancing and Indian classical dance. The sight of the steps and movements of the feet combined with the sounds being made means the audience is treated to double the performance.

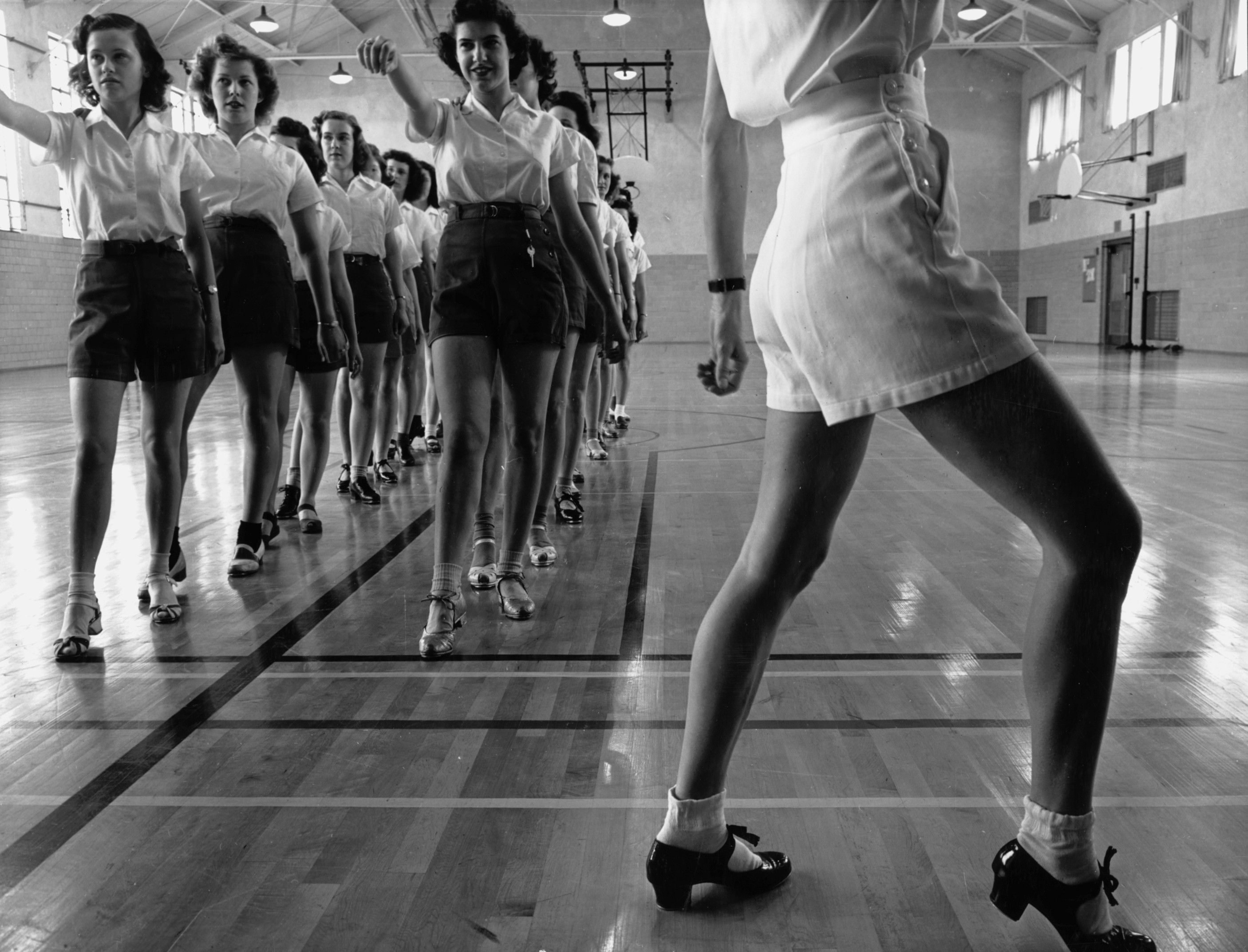

Tap dance as we know it today emerged in dance halls, with its special technique and, as it grew alongside jazz, its special rhythmic qualities. From the 1920s through to the 1950s, tap was everywhere and could be seen in films, musicals, vaudeville, and in clubs. The death of Bill “Bojangles” Robinson in 1949, one of the greatest original tappers, saw the schools in Harlem closed at noon on the day of his funeral. Three thousand people attended and thousands more stood outside.

Following the death of Robinson, there were notable changes to tap. In Broadway shows, the tap acts changed to “dream ballets” and nightclubs were closed. Popular music changed from jazz to rock and roll, and Motown took centre stage. However the 1970s saw another shift: a number of female tappers, such as Brenda Bufalino and Jane Goldberg, decided tap had to be saved and organised festivals where tap could be performed and taught again.

Tap continues to develop and move forward, with new tapping innovators and new steps to accomplish. Considering the history of tap and its rate of development, the future looks exciting for tap on stage.